Heaven & Earth

by Will Gayre. Mainstage Theatre Company directed by Don Gay at

Peacock Theatre, Salamanca Place, Hobart. November 22-30, 2013

Reviewed by Frank McKone

November 28

Canberra

critics have published reviews recently from Sydney, Melbourne and

Perth. It’s now Hobart’s turn. Mainstage is based at the Peacock

Theatre in the Salamanca Arts Centre. The author and the director are

one and the same person despite their different names. This alone

begins to explain the nature of the philosophy behind this play – that

reality is so vast, indeed infinite in its possibilities, that any

unexplainable experience may be as likely to have a cause outside what

we regard as evidential in the scientific sense as to have a place

within our concepts of the physical universe.

It’s a challenging task to make a successful drama on this kind of theme, beginning from a personal apparent déjà vu

recognition of an Italian country house while driving past on a holiday

trip from Tasmania. Tourist Dan’s obsession with finding out the

‘truth’, and the apparent truth he finds and reacts to, with tragic

consequences, is presented to us by his defence lawyer as a question for

judgement.

If all the events are no more than a mental

aberration on his part, should Dan be treated as criminally guilty of

murder? On the other hand if these events, inexplicable in normal

physical terms, really happened, then who did he actually kill – and was

this a criminal act?

There are reminiscences all the way from Carrie to The Maids

as the ‘spirit’ world seems to have effect 80 years after the causative

events on that Italian farm in World War II, but this script does not

match either of those for dramatic quality. The writer Will Gayre

provides a lengthy description in the program of his recurring dream

“from the age of about six until maybe twenty” of “standing in front of

an old double-storied [sic] farm house with a tiled roof and

cream stucco walls” which he would enter and sometimes see “people in

the rooms – never anyone I recognised and they didn’t seem at all aware

of my presence.”

Fictional tourist Dan speaks Gayre’s

words from the program notes: “Nearly ten years later I was driving

through Italy on my first major Eurpoean sojourn. Somewhere between

Pisa and Livorno I turned a corner with the river I was following and,

there, sitting on the river bank was ... the villa from my dreams!”

Bit

by bit a story develops of two couples – Dan (Alex Rigozzi) and current

girlfriend Sue (Melanie Brown), and their friends Matt (Aidan Furst)

and Jo (Bryony Hindley) who also play the roles in 1940-41 of newly

married Marko and Sophia. Sophia refuses to accept Marko's being called

up in the defence of his country, calls upon God – who seems unable to

help her – and kills her husband rather than allow him to return to

battle after his all-too-short leave. She stabs herself, but lives for

some time before dying in a mental asylum, while the local villagers

believe the violence was at the hands of unknown assailants on one side

or the other in the confusion of the war in Italy.

So

far, so good – except that in the modern time Dan’s digital photo of the

house shows a shadowy figure of a woman. Later her image has

disappeared. Then when Sue makes seriously playful sexual approaches to

Dan, some inexplicable force throws her away from him. After an

attempt to take Dan back in time by an older woman hypnotist (Carol

Devereaux) with whom Dan had previously had a relationship, Sophia

appears as a ghost to him, but a touch on the shoulder spins him around,

and it is Jo he kills.

Matt and Sue are distraught and

mystified, while it seems that Sophia had become Jo, whom the obsessed –

or rather possessed – Dan had to destroy. At this point Devereaux

appears as Dan’s defence attorney to present her concluding speech to

us, as the jury.

You can see the connection with Carrie, I guess, but you may be wondering why I mentioned Jean Genet’s The Maids. The problem for Heaven & Earth is that it is far too much like the superficial idea of horror-spirit-reality in popular genre movies like Carrie, when it needs the subtleties of psychology of The Maids

to support the weight of serious discussion of the nature of reality

which this writer seems to want to have with us. Images disappearing

from a hard drive and a character being thrown across the stage by a

mysterious force just don’t cut the mustard.

Gayre takes Shakespeare as his source – There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy

– as if we, or indeed Shakespeare, might believe Hamlet’s father’s

ghost to be literally real. Nothing inexplicable happens in Hamlet.

But Shakespeare, like Genet, understood that events can overwhelm some

people’s ability to hold onto reality, while their plays help us

understand ourselves. Gayre does no more than fall into the fad of

questioning everything just because we can.

There is

also the problem that Don Gay, director, was not able to present the

play on stage in a smoother format, rather than switching back and forth

between times and places in a repetitive and interruptive way. Yes,

it was obvious when we saw the slide of the old farmhouse that this was

now 1940/41, and now it is modern times in Don and Sue’s apartment when

that stone wall was turned around to become their sofa. Too obvious.

Though

the script itself makes this a technical staging problem, it could have

been handled better – even in the fairly limited performing space of

the Peacock Theatre – by, for example, setting aside one area for the

1940/41 period and another for modern time. Then, with lighting and

actors held in freeze positions, changes would not need actors to exit

and enter, with the occasional backstage person or the actors themselves

having to move props and furniture that I had to watch. It would also

allow space and time to be connected for us, for example by the force

that throws Sue appearing to come from Sophia’s area on the stage, and

so that the transition of Sophia into Jo might be made as Dan moves into

the 1940/41 space and time.

However, if there was one

aspect of the play that showed dramatic strength it was in the

performance of Sophia and Jo by Bryony Hindley, backed by effective work

by Aidan Furst as Marko and Matt. Hindley, at nineteen, is written up

as seeking to audition for further training. I for one would certainly

encourage her in this endeavour.

Mainstage is clearly a

small-scale company, similar to the many Canberra companies like Elbow

Theatre, Bohemian Productions and others now associated with the

development programs offered by The Street Theatre which continue to

generate new work and opportunities for practitioners, often opening up

interstate and international employment. I suppose I should conclude,

then, that there are more things, indeed, at least on earth, and perhaps

even in heaven, for such theatre companies to aspire to.

© Frank McKone, Canberra

Theatre criticism and commentary by Frank McKone, Canberra, Australia. Reviews from 1996 to 2009 were originally edited and published by The Canberra Times. Reviews since 2010 are also published on Canberra Critics' Circle at www.ccc-canberracriticscircle.blogspot.com AusStage database record at https://www.ausstage.edu.au/pages/contributor/1541

Thursday, 28 November 2013

Monday, 4 November 2013

2013: Symposium on Splinters Theatre of Spectacle. Report.

A Canberra Critics' Circle Symposium on Splinters Theatre of Spectacle

Saturday November 2, from 1.30pm to 4pm at the Canberra Museum and Gallery Theatrette.

A brief reflection by Frank McKone

Chaired by CCC convenor, Helen Musa, each of the speakers took the floor for some 20 minutes, including questions from the small but keenly interested audience. Speakers were:

Patrick Troy, one of the founders of Splinters, who remained central to Splinters’ work throughout the company’s performances from 1985 to 1996, coming from a drama background in high school and secondary college, and Canberra Youth Theatre. He provided a lively sense of the variety, energy, and sometimes conflicting forces which stimulated the work of Splinters, as well as the often difficult times of touring with little finance. Discussion arose about the place of women, including leading performers and writers such as Pauline Cady, who subsequently became co-director of Snuff Puppets in Melbourne (http://www.snuffpuppets.com/) and the photographer Katherine Pepper, whose documenting of Splinters’ performances has formed an essential part of the exhibition at the Canberra Museum and Gallery Splinters Theatre of Spectacle: Massive love of risk (28 September – December 2013) (http://www.museumsandgalleries.act.gov.au/cmag/). The current director of ACT Museums and Galleries is Shane Breynard, also a supporter of Splinters in the 1980s.

Actor/Artist Renald Navilly who worked with Splinters over many years in a role which might best be described as enabler and shaper. He made it clear that his was never an authoritarian approach: his function was to hear ideas put forward by people, welcome all ideas however diverse, encourage people to be the authors of the development of ideas, and help guide the process of selection to create a dramatic structure in performance. He spoke of the influences on his philosophy and practice such as the Living Theatre (http://www.livingtheatre.org/about/history), Jerzy Grotowksi’s Polish Laboratory Theatre (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jerzy_Grotowski) and to some extent by the work of Antonin Artaud (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theatre_of_Cruelty).

Assistant Professor Dr Geoff Hinchcliffe, Media and Graphic Design at University of Canberra, was a participant in many Splinters performances, on stage and in visual design and effects, with a background in secondary college drama and tertiary training at the Canberra School of Art. He spoke on the visual culture developed by Splinters, but also took up discussion of the group collective approach which made Splinters into a social unit open to welcoming new participants and changing ideas, noting that possibly some 1000 people were involved over the decade.

Canberra author Joel Swadling spoke on the biography he is writing about the late David Branson, a founding member of Splinters as well as a key figure in a wide range of theatrical and musical work as director and performer until his tragic accidental death in 2001. As the work on the biography progresses, from a detailed study of nine boxes of Branson’s papers – now held in the ACT Heritage Library Manuscript Collection http://www.library.act.gov.au/find/history/search/Manuscript_Collections/David_Branson – and through extensive interviews with many of the people who knew and worked with Branson, a picture is forming of the quality and importance of his contribution to theatre arts in Canberra, Australia and internationally.

This writer, educator/theatre critic Frank McKone, spoke on the issue which others also alluded to: how did Splinters’ often anarchic approach to theatre arise in Canberra, the capital city largely populated by public servants, and seen by outsiders as a planned city with no soul. He proposed a theory that in 1968, the 19th year of conservative government, the accidental rise to the Prime Ministership of John Gorton, described as a man who liked to portray himself as a man of the people who enjoyed a beer and a gamble, with a bit of a "larrikin" streak about him, in stark contrast to the previous Liberal Party PMs, stirred the conventional public servants, by osmosis, to reject the control of Canberra’s education system by the authoritarian New South Wales Department, and to demand our own ACT Schools Authority. In starting a new system from scratch, including offering the first Drama courses in Australia at matriculation level, teachers found themselves with the freedom to “negotiate the curriculum” with their students from 1972, very much in the manner that Renald Navilly described in his work with Splinters participants from 1985.

The curator of the CMAG exhibition which included this Symposium, former Splinters member Gavin Findlay who joined after being impressed by the work they presented at the Performance Space, Redfern in Sydney, (http://www.performancespace.com.au/us/history/) then spoke on the archiving of Splinters records and how the materials and history form the basis of his doctoral research designed to recognise the place of Splinters in 20th Century theatre, nationally and internationally.

In discussion, as well as the developments in the schools in the 1970s, the importance of the establishment by Carol Woodrow (http://www.womenaustralia.info/biogs/AWE4882b.htm) of Canberra Children’s Theatre, Reid House Theatre Workshop, Canberra Youth Theatre, The Jigsaw Company, and The Fools’ Gallery during the same period, showed that Canberra was developing its own sense of authorship in both the educational and professional theatre circles, so that by the mid-1980s there was fertile ground for Splinters to grow among young people committed to the crossover of theatre and visual arts.

© Frank McKone, Canberra

Saturday November 2, from 1.30pm to 4pm at the Canberra Museum and Gallery Theatrette.

A brief reflection by Frank McKone

Chaired by CCC convenor, Helen Musa, each of the speakers took the floor for some 20 minutes, including questions from the small but keenly interested audience. Speakers were:

Patrick Troy, one of the founders of Splinters, who remained central to Splinters’ work throughout the company’s performances from 1985 to 1996, coming from a drama background in high school and secondary college, and Canberra Youth Theatre. He provided a lively sense of the variety, energy, and sometimes conflicting forces which stimulated the work of Splinters, as well as the often difficult times of touring with little finance. Discussion arose about the place of women, including leading performers and writers such as Pauline Cady, who subsequently became co-director of Snuff Puppets in Melbourne (http://www.snuffpuppets.com/) and the photographer Katherine Pepper, whose documenting of Splinters’ performances has formed an essential part of the exhibition at the Canberra Museum and Gallery Splinters Theatre of Spectacle: Massive love of risk (28 September – December 2013) (http://www.museumsandgalleries.act.gov.au/cmag/). The current director of ACT Museums and Galleries is Shane Breynard, also a supporter of Splinters in the 1980s.

Actor/Artist Renald Navilly who worked with Splinters over many years in a role which might best be described as enabler and shaper. He made it clear that his was never an authoritarian approach: his function was to hear ideas put forward by people, welcome all ideas however diverse, encourage people to be the authors of the development of ideas, and help guide the process of selection to create a dramatic structure in performance. He spoke of the influences on his philosophy and practice such as the Living Theatre (http://www.livingtheatre.org/about/history), Jerzy Grotowksi’s Polish Laboratory Theatre (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jerzy_Grotowski) and to some extent by the work of Antonin Artaud (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theatre_of_Cruelty).

Assistant Professor Dr Geoff Hinchcliffe, Media and Graphic Design at University of Canberra, was a participant in many Splinters performances, on stage and in visual design and effects, with a background in secondary college drama and tertiary training at the Canberra School of Art. He spoke on the visual culture developed by Splinters, but also took up discussion of the group collective approach which made Splinters into a social unit open to welcoming new participants and changing ideas, noting that possibly some 1000 people were involved over the decade.

Canberra author Joel Swadling spoke on the biography he is writing about the late David Branson, a founding member of Splinters as well as a key figure in a wide range of theatrical and musical work as director and performer until his tragic accidental death in 2001. As the work on the biography progresses, from a detailed study of nine boxes of Branson’s papers – now held in the ACT Heritage Library Manuscript Collection http://www.library.act.gov.au/find/history/search/Manuscript_Collections/David_Branson – and through extensive interviews with many of the people who knew and worked with Branson, a picture is forming of the quality and importance of his contribution to theatre arts in Canberra, Australia and internationally.

This writer, educator/theatre critic Frank McKone, spoke on the issue which others also alluded to: how did Splinters’ often anarchic approach to theatre arise in Canberra, the capital city largely populated by public servants, and seen by outsiders as a planned city with no soul. He proposed a theory that in 1968, the 19th year of conservative government, the accidental rise to the Prime Ministership of John Gorton, described as a man who liked to portray himself as a man of the people who enjoyed a beer and a gamble, with a bit of a "larrikin" streak about him, in stark contrast to the previous Liberal Party PMs, stirred the conventional public servants, by osmosis, to reject the control of Canberra’s education system by the authoritarian New South Wales Department, and to demand our own ACT Schools Authority. In starting a new system from scratch, including offering the first Drama courses in Australia at matriculation level, teachers found themselves with the freedom to “negotiate the curriculum” with their students from 1972, very much in the manner that Renald Navilly described in his work with Splinters participants from 1985.

The curator of the CMAG exhibition which included this Symposium, former Splinters member Gavin Findlay who joined after being impressed by the work they presented at the Performance Space, Redfern in Sydney, (http://www.performancespace.com.au/us/history/) then spoke on the archiving of Splinters records and how the materials and history form the basis of his doctoral research designed to recognise the place of Splinters in 20th Century theatre, nationally and internationally.

In discussion, as well as the developments in the schools in the 1970s, the importance of the establishment by Carol Woodrow (http://www.womenaustralia.info/biogs/AWE4882b.htm) of Canberra Children’s Theatre, Reid House Theatre Workshop, Canberra Youth Theatre, The Jigsaw Company, and The Fools’ Gallery during the same period, showed that Canberra was developing its own sense of authorship in both the educational and professional theatre circles, so that by the mid-1980s there was fertile ground for Splinters to grow among young people committed to the crossover of theatre and visual arts.

© Frank McKone, Canberra

Wednesday, 30 October 2013

2013: Canberra Critics' Circle symposium on Splinters Theatre of Spectacle - Preview

|

| Splinters: Faust |

Splinters:

only in Canberra?

A Canberra Critics' Circle symposium on Splinters

Theatre of Spectacle

Saturday November 2

from 1.30pm to 4pm

at The Canberra Museum

and Gallery Theatrette.

FREE event. RSVP via cmagbookings@act.gov.au or

6207 3968.

Splinters Theatre of Spectacle was an Australian Performance Troupe formed in Canberra in 1985 by David Branson, Patrick Troy, Ross Cameron, and John Utans, that was known for large outdoor spectacles.[1] Between 1985 and 1996, Splinters produced more than 20 works that played at Australian theatre festivals. In 1992, they produced Cathedral of Flesh which won the Best Promenade Theatre Performance Award, at the Adelaide Fringe Festival.[2]

[Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Splinters_Theatre_of_Spectacle ]

Speakers will include:

Patrick Troy, one of

the founders of Splinters.

Actor/Artist Renald Navilly on Splinters as a theatre process.

Actor/Artist Renald Navilly on Splinters as a theatre process.

Curator, former Splinters member Gavin Findlay on the

archiving of Splinters records.

Canberra author Joel Swadling on the biography he is writing about the late David Branson.

Educator/Theatre critic Frank McKone on the influence of ACT College arts and drama on the development of Splinters.

Assistant Professor Dr Geoff Hinchcliffe on the visual culture of Splinters

Canberra author Joel Swadling on the biography he is writing about the late David Branson.

Educator/Theatre critic Frank McKone on the influence of ACT College arts and drama on the development of Splinters.

Assistant Professor Dr Geoff Hinchcliffe on the visual culture of Splinters

Canberra Critics' Circle convener Helen Musa in the chair.

© Frank McKone, Canberra

© Frank McKone, Canberra

2013: The Comedy of Errors by William Shakespeare

|

| Imara Savage - Director |

Reviewed by Frank McKone

October 30

I suspect that William Shakespeare’s move from staid and sensible Stratford-on-Avon to lewd, lascivious and libellous London paved the way for the horror faced by Antipholus and his stolid, mercantile merchant father from Syracuse when they landed in energetic, excessive, sexually-charged Ephesus. It must have been quite a revelation for Shakespeare to discover that his London of 1593 was not very different from what Plautus, some 100-200 years BC, had already described in his fictional Greek city of Epidamnum, in his play Menaechmi.

So for us it is a wonder to see the brilliance of Shakespeare’s words reveal how little different is the world of, say, Sydney’s Kings Cross after another 420 years. Like Plautus, Shakespeare understood that a farcical treatment was the only way to come to terms with both the light and dark sides of such a community. In this Comedy of Errors, Savage Witt is brought to bear with unerring aim.

To follow my line of thinking you need a copy of the wonderful program with its extensive background to the production. It adds enormously to the satisfaction of seeing the play to read, far beyond the usual plot synopsis and director’s notes, source quotes and essays on comedy, farce, Plautus, Shakespeare’s Ephesus, the place of the classics, Kings Cross as explained by Louis Nowra, The Comedy of Errors as explained by Andy McLean, more details on Shakespeare’s sources, and the concept drawings of the characters by Pip Runciman.

The result on stage is near perfection. Every nuance of Shakespeare’s intention in each line spoken and each action taken by each character is brought into a shining spotlight. Now it is absolutely clear that this is not a young playwright’s immature imitation of a Latin classic. This is farce precisely performed to the point of satire of human society.

The casting is exquisite. The make-up and the costuming of the two sets of identical twins is so well done that, until the final scene, it was hard to believe that there were four actors rather than two doubling up the roles. The set consisting of even more doors across the stage than I have ever thought possible – and added to by left and right entrances upstage and downstage – made this necessary element of stage farce into a character in its own right. And no-one will ever forget props like the sun-tan machine, the hot electric iron and especially the washing machine and its sudsy servant Dromio – a scene which can justifiably claim the loudest laugh of the night.

There has been a long tradition in Australian acting of rumbustious physical theatre, fully endorsed by Bell Shakespeare and training at NIDA and in all the institutions since the 1960s, which comes to a peak of entertainment and theatrical maturity in this production of The Comedy of Errors.

If you can’t get to see it in Canberra, you have one more chance at the Sydney Opera House Playhouse from November 12 to December 7 – the last of 32 venues in the Playing Australia touring program. Do your best not to miss it – and don’t forget to buy a program.

© Frank McKone, Canberra

| ||

| Renato Musolino, Nathan O'Keefe, Septimus Caton, Hazem Shammas as Dromio and Antipholus of Syracuse and Dromio and Antipholus of Ephesus, with Demetrios Sirilas as Angelo (upstage) |

|

| Nathan O'Keefe (Antipholus of Syracuse) with Jude Henshall as Luciana |

|

| Suzannah McDonald as Courtesan |

2013: Come Alive at the National Museum of Australia

Come Alive

at the National Museum of Australia. Artistic Director, Peter Wilkins;

Manager, Mitch Preston, NMA Learning Services and Community Outreach.

October 28 – November 1, 2013.

Commentary by Frank McKone

This is the fourth annual Come Alive festival in which nine Canberra schools present 11 performances written and performed by students based on their observations of exhibits currently on display in the National Museum of Australia.

The festival is an initiative taken under the Museum’s keen interest in IMTAL, the International Museum Theatre Alliance, whose annual conference has just been held at the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, described (pre-conference) as follows:

The 2013 IMTAL Global Conference will focus on creativity and innovation in today’s Museum Theatre. In 2013, Museum Theatre is a proven, tested, educational approach in the field of museum studies. It is also an art form bringing the best of performance to museum visitors of all ages. But how is the field continuing to evolve? The 2013 Global conference will bring together practitioners, researchers, performers, and museum professionals from around the world to discuss, debate, present, and share examples of how the field is evolving and innovating.

http://www.imtal.org/Default.aspx?pageId=1329539&eventId=546003&EventViewMode=EventDetails

As far as I know, Wilkins’ approach at the NMA is rare, if not unique. He combines the learning about Australia’s social history with the learning of the practice of theatre by putting the students in the position of researchers, writers and performers.

In one show I saw today (October 30), Melrose High School took up the question of whether each of three women whose stories are on display – Holocaust survivor Olga Horak, Annette Kellerman who was the first woman to swim the English Channel and stood up for women’s rights early in the last century, and Ida Prosser-Fenn, a missionary and nurse in Papua New Guinea through the 1940s and 50s – should be allowed into heaven. The last laugh on the gatekeeper (a woman, not St Peter) was that all had satisfied Heaven’s requirements – but Olga Horak is still alive, volunteering at the Jewish Museum in Sydney. So they promised she would be let in when she dies. Their play is called The Final Reward.

Canberra College students took an entirely different angle. The Saw Doctor’s wagon was the mobile home and workshop of Harold Wright, who started travelling the roads of rural Australia during the 1930s Depression. After migrating from England to Australia in 1930, Wright began walking Queensland roads to find work. In 1935, he used the little money he had saved to convert a horsedrawn wagon into a combined workshop and home. Over the next 34 years, as he travelled throughout the farmlands and towns of north-west Victoria and New South Wales sharpening knives and blades, Wright made updates and changes to his wagon, promoting himself as ‘The Saw Doctor’.

[http://www.nma.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/353629/Museum_Issue2_Sep2012_Well-travelled.pdf]

Instead of re-telling the story of Harold Wright, the students turned him into “Tinker Tom” whose tractor and wagon became a time-travel machine to take an audience of second and third-graders back to the 1956 Melbourne Olympics and one of the first outside television broadcasts in Australia, to the burning of their mining licences by the gold diggers at the Eureka Stockade, to the convict days of the female factory, and even back to the era of the dinosaurs. Humorous and even quite absurdist, Tinker Tom’s Travels will go into primary schools and I’m sure will succeed in its prime purpose of engendering a sense of history through the fun of time travel.

There’s no doubt in my mind that these examples show that Peter Wilkins succeeds in encouraging the creativity and innovation that IMTAL seeks. But it struck me watching today that there is a further level of education going on here. The young people participating in museum theatre are engaged in the very multicultural life which the National Museum encapsulates as the core of life in Australia. Writing and performing their own plays takes the students out of their personal circumstances, and perhaps out of their assumptions, into the lives of a great variety of people across the country and across time. Within the groups performing today the variety of cultures in our society was clearly represented, all working together to explore their Australian heritage – and watching other groups from other schools travelling a similar journey.

So I see Come Alive not so much about learning about history, but being history through drama. It was, perhaps, the Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner, famous for his Seven Intelligences, who first established the importance of education through museums. Come Alive, I suggest, is proof in action.

© Frank McKone, Canberra

Commentary by Frank McKone

This is the fourth annual Come Alive festival in which nine Canberra schools present 11 performances written and performed by students based on their observations of exhibits currently on display in the National Museum of Australia.

The festival is an initiative taken under the Museum’s keen interest in IMTAL, the International Museum Theatre Alliance, whose annual conference has just been held at the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, described (pre-conference) as follows:

The 2013 IMTAL Global Conference will focus on creativity and innovation in today’s Museum Theatre. In 2013, Museum Theatre is a proven, tested, educational approach in the field of museum studies. It is also an art form bringing the best of performance to museum visitors of all ages. But how is the field continuing to evolve? The 2013 Global conference will bring together practitioners, researchers, performers, and museum professionals from around the world to discuss, debate, present, and share examples of how the field is evolving and innovating.

http://www.imtal.org/Default.aspx?pageId=1329539&eventId=546003&EventViewMode=EventDetails

As far as I know, Wilkins’ approach at the NMA is rare, if not unique. He combines the learning about Australia’s social history with the learning of the practice of theatre by putting the students in the position of researchers, writers and performers.

In one show I saw today (October 30), Melrose High School took up the question of whether each of three women whose stories are on display – Holocaust survivor Olga Horak, Annette Kellerman who was the first woman to swim the English Channel and stood up for women’s rights early in the last century, and Ida Prosser-Fenn, a missionary and nurse in Papua New Guinea through the 1940s and 50s – should be allowed into heaven. The last laugh on the gatekeeper (a woman, not St Peter) was that all had satisfied Heaven’s requirements – but Olga Horak is still alive, volunteering at the Jewish Museum in Sydney. So they promised she would be let in when she dies. Their play is called The Final Reward.

Canberra College students took an entirely different angle. The Saw Doctor’s wagon was the mobile home and workshop of Harold Wright, who started travelling the roads of rural Australia during the 1930s Depression. After migrating from England to Australia in 1930, Wright began walking Queensland roads to find work. In 1935, he used the little money he had saved to convert a horsedrawn wagon into a combined workshop and home. Over the next 34 years, as he travelled throughout the farmlands and towns of north-west Victoria and New South Wales sharpening knives and blades, Wright made updates and changes to his wagon, promoting himself as ‘The Saw Doctor’.

[http://www.nma.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/353629/Museum_Issue2_Sep2012_Well-travelled.pdf]

Instead of re-telling the story of Harold Wright, the students turned him into “Tinker Tom” whose tractor and wagon became a time-travel machine to take an audience of second and third-graders back to the 1956 Melbourne Olympics and one of the first outside television broadcasts in Australia, to the burning of their mining licences by the gold diggers at the Eureka Stockade, to the convict days of the female factory, and even back to the era of the dinosaurs. Humorous and even quite absurdist, Tinker Tom’s Travels will go into primary schools and I’m sure will succeed in its prime purpose of engendering a sense of history through the fun of time travel.

There’s no doubt in my mind that these examples show that Peter Wilkins succeeds in encouraging the creativity and innovation that IMTAL seeks. But it struck me watching today that there is a further level of education going on here. The young people participating in museum theatre are engaged in the very multicultural life which the National Museum encapsulates as the core of life in Australia. Writing and performing their own plays takes the students out of their personal circumstances, and perhaps out of their assumptions, into the lives of a great variety of people across the country and across time. Within the groups performing today the variety of cultures in our society was clearly represented, all working together to explore their Australian heritage – and watching other groups from other schools travelling a similar journey.

So I see Come Alive not so much about learning about history, but being history through drama. It was, perhaps, the Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner, famous for his Seven Intelligences, who first established the importance of education through museums. Come Alive, I suggest, is proof in action.

© Frank McKone, Canberra

Tuesday, 15 October 2013

2013: Whoops! – The Wharf Revue by Jonathan Biggins, Drew Forsythe and Phillip Scott

Whoops! – The Wharf Revue by Jonathan Biggins, Drew Forsythe and Phillip Scott, with Amanda Bishop and Simon Burke. Musical director and accompanist, Andrew Worboys; sound and video designer, David Bergman; video artist, Todd Decker. Sydney Theatre Company at Canberra Theatre Playhouse, October 15-19, 2013.

Reviewed by Frank McKone

October 15

The central theme of last night’s Revue, so successfully expressed in the lengthy political satire based on the absurdist play Rosencrantz and Guilderstern Are Dead, was thoroughly confirmed by the explanation in today’s Canberra Times (Times 2, p.4) by economics correspondent Peter Martin of why the award of a Nobel prize to the economists Eugene Fama, Robert Shiller and Lars Hansen is so invaluable.

As Martin reports, Australian economists Richard Holden at the University of NSW and Justin Wolfers at the Brookings Institution summed up the findings online as being that financial markets are efficient (Fama), except when they’re not (Shiller), and that we have empirical evidence to prove it (Hansen).

Though not all the fifteen items in this year’s Revue were as good as last year’s Fall of the Garden of Earthly Delights, (the National Rifle Association country and western song, and even the ever-giggling Dalai Lama were a bit ordinary as satire goes), this year the “new maturity in the writing” which I noted last year, and the quality of the video work by David Bergman and Todd Decker, have become established.

The characterisations of Tony Abbott’s hypocrisy, Gina Rinehart’s pontifications, Bob Katter’s country pub pretence, and Julia Gillard as an operatic Carmen were all on the money (just to maintain the economic metaphor). In fact Amanda Bishop’s Gillard Habanera swansong, in that long slinky brilliant red gown, stirred the house to the same kind of reponse that we saw in the Sydney Opera House when Anne Summers interviewed the real Julia on September 30, 2013: (http://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-09-30/live-coverage-julia-gillard-at-the-sydney-opera-house/4989792).

This year, too, the whole company’s singing throughout, perhaps especially in The Tale of Eddie Obeid and The Wizard of Oz (who lives in The Lodge), demonstrated the point that effective satire depends on top quality performance. For me the ultimate moment, or rather very long moments, came at the opening in excruciating silence of Rosencrantz and Guilderstern Instead which developed deeper and deeper into the sense that there is no possibility of these sidelined characters ever being able to understand the central characters of politics because, as the Nobel-winning economists have empirically proved about financial markets, politics make sense except when they don’t.

Whoops! leaves us all realising that we are all sidelined like R&G. The laughter and extensive whoops of appreciation at the curtain calls can’t paper over the cracks which reveal the dark side of political life, which we are all engaged in whether we like it or not. It’s only through art and science, as the Revue showed so well in the item The Culture Wars, that this kind of truth can be expressed.

We need the annual Wharf Revue, at least to be able to laugh at the absurdity.

© Frank McKone, Canberra

Tuesday, 8 October 2013

2013: The 39 Steps adapted by Patrick Barlow

|

| Mike Smith and Anna Burgess |

|

| Sam Haft and Michael Lindner |

Reviewed by Frank McKone

October 8

Having been born in the opening salvos of World War II, a period of history I prefer to forget, I never read Buchan’s World War I novel or saw Hitchcock’s 1935 film, so I didn’t recognise the allusion to North by North West as Richard Hannay (nicely played by Mike Smith) scooted around Scotland on a mission to prove his innocence on a murder charge and to save Britain.

If you didn’t either, I’m with you, but there apparently are many still fascinated by spy stories of that era, and happy to enjoy the fun. This adaptation from a concept based on a film of the novel turns out to be an example of English farce – a spoof of a spy story – very funny in parts (like the curate’s egg), but otherwise completely inconsequential.

The strength of this production is not only in the vocal and movement skills of all the actors – Mike Smith, Anna Burgess, Sam Haft and Michael Lindner – in the rapidity with which they changed costumes and characters for the innumerable short cameo scenes.

The major award must go to Alana Scanlan for her remarkable choreography. Burgess’s first role as the murdered spy Annabella was made into a quite extraordinary character by her movement style – even when dead! And Haft and Lindner had all the right dance steps to be justifiably applauded as they took to the London Palladium stage.

The English have always made fun of war, from Shakespeare to the Goon Show, and even to the point where it’s funny not to mention it, but I found too much of The 39 Steps is dated and cliché. The only point where it moved a fraction of the way to more interesting satire was the election speech made by the escapee Hannay who the lower-class locals assume to be their famous upper-class visiting speaker. There’s even a sort-of nod here, reversing the social classes, to Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator but the point is soon lost in the farce that follows.

Since my own (very minimal and entirely amateur) acting career included playing Mr Mole in the English farce Love’s a Luxury (by Guy Paxton and Edward V. Hoile – see http://www.ba-education.com/for/entertainment/sjt/lovesaluxury.html for some interesting reading), I can’t pretend to complain. In fact I laughed along with a substantial audience at The Q, but came out wondering about whether the intention behind this adaptation was to use an expressionist style to turn farce into satire – which really didn’t work – or to simply indulge in a cultish fascination with Hitchcock and spies, which went over my head.

And I can’t complain about the performances. Very entertaining and done with professional precision.

© Frank McKone, Canberra

Saturday, 5 October 2013

2013: Emily Eyefinger based on the books by Duncan Ball

Emily Eyefinger

based on the books by Duncan Ball adapted by Eva Di Cesare, Sandra

Eldridge & Tim McGarry. Monkey Baa Theatre Company:

Director John Saunders

Designer Mark Thompson

Lighting Designer Martin Kinnane

Sound Designer Rowan Karrer

Dramaturge Caleb Lewis

Animation Andrew Hagan

at The Street Theatre, Canberra, October 1 – 5, 2013.

Reviewed by Frank McKone

October 5

Since Monkey Baa makes considerable claims http://monkeybaa.com.au/info/history/) such as Founding members Eva Di Cesare, Sandra Eldridge and Tim McGarry established Monkey Baa to raise the bar of work for young people in Australia..., their production of Emily Eyefinger needs some detailed consideration.

The style of acting and the construction of the storyline can only be described as zany pantomime. Like traditional British pantomime there was nearly as much for the adults to recognise and enjoy in the story of entering the tomb in the Ancient Caves of Tutenkamouse, with its mystery of the curse upon the first to enter, and in the characterisations especially of Great Aunt Olympia and the evil Arthur Crim, as for the target audience of 5 to 10 year olds.

There were some younger children in the audience when I saw it, and they were a bit frightened by some of the sound effects and Arthur Crim’s coming off stage into the audience – and they probably didn’t follow the story very well, especially since the transitions between scenes were often unpredictable. In fact, in academic terms, “zany” could almost be classed as “absurdism”.

On the other hand the older children clearly got the hang of the visual jokes and clowning, and recognised the reactions of the young characters, especially of Malcolm sulking because his mouse researcher father insisted he wear a mouse costume all the time, and of Emily’s feeling that she had lost her identity because her finger with its third eye had become the centre of attention. The fact that they both took control of their lives – Malcolm taking his mouse head off in front of his father, and Emily realising she should keep her eyefinger and even enjoy being different rather than ‘normal’ – was an effective educational message, presented as a natural part of the action without obvious moralising.

On the point of standards (raising the bar), the acting was certainly up to high chin up level in characterisation and movement skills, and I was impressed with the set, props, sound and video design (and technical quality), especially considering the limitations you might expect when touring.

Having seen only one Monkey Baa production, I can’t say anything about the quality of their work overall, but within the range of the style of Emily Eyefinger, this production is certainly at a very good professional standard.

© Frank McKone, Canberra

Director John Saunders

Designer Mark Thompson

Lighting Designer Martin Kinnane

Sound Designer Rowan Karrer

Dramaturge Caleb Lewis

Animation Andrew Hagan

at The Street Theatre, Canberra, October 1 – 5, 2013.

Reviewed by Frank McKone

October 5

Since Monkey Baa makes considerable claims http://monkeybaa.com.au/info/history/) such as Founding members Eva Di Cesare, Sandra Eldridge and Tim McGarry established Monkey Baa to raise the bar of work for young people in Australia..., their production of Emily Eyefinger needs some detailed consideration.

The style of acting and the construction of the storyline can only be described as zany pantomime. Like traditional British pantomime there was nearly as much for the adults to recognise and enjoy in the story of entering the tomb in the Ancient Caves of Tutenkamouse, with its mystery of the curse upon the first to enter, and in the characterisations especially of Great Aunt Olympia and the evil Arthur Crim, as for the target audience of 5 to 10 year olds.

There were some younger children in the audience when I saw it, and they were a bit frightened by some of the sound effects and Arthur Crim’s coming off stage into the audience – and they probably didn’t follow the story very well, especially since the transitions between scenes were often unpredictable. In fact, in academic terms, “zany” could almost be classed as “absurdism”.

On the other hand the older children clearly got the hang of the visual jokes and clowning, and recognised the reactions of the young characters, especially of Malcolm sulking because his mouse researcher father insisted he wear a mouse costume all the time, and of Emily’s feeling that she had lost her identity because her finger with its third eye had become the centre of attention. The fact that they both took control of their lives – Malcolm taking his mouse head off in front of his father, and Emily realising she should keep her eyefinger and even enjoy being different rather than ‘normal’ – was an effective educational message, presented as a natural part of the action without obvious moralising.

On the point of standards (raising the bar), the acting was certainly up to high chin up level in characterisation and movement skills, and I was impressed with the set, props, sound and video design (and technical quality), especially considering the limitations you might expect when touring.

Having seen only one Monkey Baa production, I can’t say anything about the quality of their work overall, but within the range of the style of Emily Eyefinger, this production is certainly at a very good professional standard.

© Frank McKone, Canberra

Thursday, 3 October 2013

2013: The Book Club by Rodney Fisher

The Book Club by Rodney Fisher, from the play by Roger

Hall. Performed by Amanda Muggleton, direction and set design by Rodney

Fisher. Produced by Christine Harris and HIT Productions at The Q,

Queanbeyan Performing Arts Centre, October 3-5, 2013.

Reviewed by Frank McKone

October 3

Amanda Muggleton is justifiably the darling of Queanbeyan, despite making an awful error in the city’s 175th Birthday year. Speaking to the audience after two curtain calls, thanking us for being so responsive (which indeed we were), she opined “I just love coming to Canberra!” Oops! After all Canberra is a mere 100 years old this year.

But no matter. We understood and we appreciated her role as our favourite actor, while someone in the front row explained politely to her that Queanbeyan has an identity of its own.

Apart from her fortitude in performing solo for two acts of an hour and a quarter each, which in itself commands our respect, her flexibility and comic ingenuity in playing the role of Deborah, who also acts out all the characters from the book club, in her family and in her breakaway relationship with the author, Michael, after inviting him as speaker, was a wonderful demonstration of her acting skills.

Yet there was more. The warmth and attention for which she praised us in the audience only developed because of Amanda’s openness to our reactions. Instead of strictly playing the script and the character, she was able to smoothly make the transition to ad libbing and communicating with us as herself and then slipping back into role as Deborah. Only once did she have to repeat a line to cue herself back into the official script.

So we were treated to two performances in one – Amanda and Deborah – and we loved them both.

The play is cleverly written using the books the book club decides to discuss as a through-line parallel to Deborah’s marital and extra-marital story. This allows for references to change according to the authors now in vogue – Tim Winton does well out of this – as well as keeping those in the canon – particularly To Kill a Mockingbird and Anna Karenina – which are essential to our understanding of Deborah’s emotional life. I guess it is this appeal to the reading audience which makes the play so appropriate for middle-class Queanbeyan – Canberra.

I would also add, though, that the The Q theatre played its role. It is perhaps the only local venue that is comfortable, has the right sight-lines and raking of the seating, and responsive acoustics, which create an intimate inclusive feeling for several hundred people.

The Q management is friendly and runs smoothly, and the director Stephen Pike has made an excellent choice in bringing The Book Club here.

But I have to end on the only problematic note, which I have had to mention on some previous occasions. Christine Harris likes to have her name publicly attached to her production company HIT Productions, but does her actors, designers and technical staff a great disservice by providing no more than a poster in the foyer with limited information. Any theatre production is a cooperative venture, and all the participants should be properly publicly acknowledged.

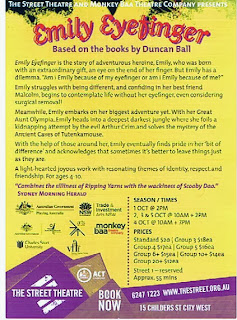

As a model for HIT Productions, I suggest Ms Harris should take a leaf from Caroline Stacey’s book at The Street Theatre, and provide a simple but colourful small flyer to go with each ticket sale (or at least a pile of them in the foyer for people to take if they wish). So I’m including here a picture of the flyer for The Street’s current production of Emily Eyefinger as an example, since I don’t have a program picture for The Book Club.

However, don’t let my concern on this point stop you from thoroughly enjoying Amanda Muggelton in The Book Club at The Q.

© Frank McKone, Canberra

Reviewed by Frank McKone

October 3

Amanda Muggleton is justifiably the darling of Queanbeyan, despite making an awful error in the city’s 175th Birthday year. Speaking to the audience after two curtain calls, thanking us for being so responsive (which indeed we were), she opined “I just love coming to Canberra!” Oops! After all Canberra is a mere 100 years old this year.

But no matter. We understood and we appreciated her role as our favourite actor, while someone in the front row explained politely to her that Queanbeyan has an identity of its own.

Apart from her fortitude in performing solo for two acts of an hour and a quarter each, which in itself commands our respect, her flexibility and comic ingenuity in playing the role of Deborah, who also acts out all the characters from the book club, in her family and in her breakaway relationship with the author, Michael, after inviting him as speaker, was a wonderful demonstration of her acting skills.

Yet there was more. The warmth and attention for which she praised us in the audience only developed because of Amanda’s openness to our reactions. Instead of strictly playing the script and the character, she was able to smoothly make the transition to ad libbing and communicating with us as herself and then slipping back into role as Deborah. Only once did she have to repeat a line to cue herself back into the official script.

So we were treated to two performances in one – Amanda and Deborah – and we loved them both.

The play is cleverly written using the books the book club decides to discuss as a through-line parallel to Deborah’s marital and extra-marital story. This allows for references to change according to the authors now in vogue – Tim Winton does well out of this – as well as keeping those in the canon – particularly To Kill a Mockingbird and Anna Karenina – which are essential to our understanding of Deborah’s emotional life. I guess it is this appeal to the reading audience which makes the play so appropriate for middle-class Queanbeyan – Canberra.

I would also add, though, that the The Q theatre played its role. It is perhaps the only local venue that is comfortable, has the right sight-lines and raking of the seating, and responsive acoustics, which create an intimate inclusive feeling for several hundred people.

The Q management is friendly and runs smoothly, and the director Stephen Pike has made an excellent choice in bringing The Book Club here.

But I have to end on the only problematic note, which I have had to mention on some previous occasions. Christine Harris likes to have her name publicly attached to her production company HIT Productions, but does her actors, designers and technical staff a great disservice by providing no more than a poster in the foyer with limited information. Any theatre production is a cooperative venture, and all the participants should be properly publicly acknowledged.

As a model for HIT Productions, I suggest Ms Harris should take a leaf from Caroline Stacey’s book at The Street Theatre, and provide a simple but colourful small flyer to go with each ticket sale (or at least a pile of them in the foyer for people to take if they wish). So I’m including here a picture of the flyer for The Street’s current production of Emily Eyefinger as an example, since I don’t have a program picture for The Book Club.

However, don’t let my concern on this point stop you from thoroughly enjoying Amanda Muggelton in The Book Club at The Q.

© Frank McKone, Canberra

Wednesday, 2 October 2013

2013: Brief Encounter by Noël Coward

|

| Program cover image: 'Kiss'. Photo: Simon Turtle |

Reviewed by Frank McKone

October 2

When Noël Coward rewrote his 1936 stage play Still Life in 1945 as the script for the film Brief Encounter, I was just 4. I had seen Bambi and Dumbo the Elephant, but missed Brief Encounter – and remained largely unaware of the film ever since.

Growing up in the 1950s, I became very aware of Noël Coward, but only for his songs, particularly Mad Dogs and Englishmen (for its anti-colonial political content) and Don’t Let Your Daughter on the Stage, Mrs Worthington which informed my drama work for the rest of my life.

Now, suddenly, in my maturity, I have been given a new appreciation of Coward, the playwright, by two productions: Private Lives at Belvoir (Canberra Critics’ Circle Tuesday, October 2, 2012) and now Brief Encounter by Kneehigh.

After the Cockney-style bit of song and dance to entertain us while settling in our seats, the beginning of the actual play reminded me of Woody Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985). Without knowing the script of Brief Encounter beforehand I was not expecting to be treated as if I were in a cinema (the Palladium), with the two central characters Laura Jesson (Michelle Nightingale) and Alec Harvey (Jim Sturgeon) in our front row spotlit by the ushers’ torches as they seem to have a lovers’ tiff about whether they love each other.

(I digress slightly to point out that the Palladium Cinema was closed on 3rd April 1938, so even this 1945 script had to look back to its 1936 original to make a Coward in-joke about the Palladium Cinema being too expensive upstairs – a comparison with the famous Palladium Theatre, which is still extant today and is probably too expensive downstairs.)

The connection with Woody Allen’s film is that as Laura leaves the cinema, she walks up on to the stage towards a scrim on which is projected her husband Fred (Joe Alessi) waiting for her at home. She parts the scrim, and simultaneously appears in the movie with Fred, while Alec watches. The theatrical trick immediately gained the audience’s applause, and our interest in these characters’ story was engaged.

The style of this production was now firmly established: movement became dance, dialogue was timed to the music, and songs were an essential part of the action. Ordinary ideas of reality were tested at every turn, from Laura’s children being puppets, a toy train puffing out real smoke, crashing seas on the film screen seeming to drown characters in emotion on stage, even a whole express train passing through on film projected on a scrim rushed across the stage by a railway guard – in fact so many such devices that I would need to see the production several times to catch up with all the fascinating details.

And it’s certainly a production that deserves to be seen more than once. I’m sure it would be more enjoyable each time. On the first sighting each trick was a surprise, but on subsequent viewing it would be the anticipation and recognition, and the testing of your memory that would be exciting. And indeed, like watching a circus, there would be the adrenalin rush of fearing that a trick might fail, especially when you know that this production has been touring for some five years now.

The real surprise of this kind of choreographed staging was that the feelings of the two middle-class protagonists – each married and having to deal with their sense of guilt and propriety – were enhanced, especially through the comic contrasts of the lower class characters’ relationships. Almost Shakespearean, in fact, and demanding of the performers the same kind of precision of characterisation and timing. Not a beat was missed by anyone.

So I began wondering what had Emma Rice done to Noël Coward’s original conception. Was this a modernisation, even though everything we saw was “retro”, as in 1936? But then how did references get in like the two soldiers, full – to the point of being threatening – with their sense of self-importance because they were “willing to lay down our lives for you”; or mention of Spitfires, or Judy Garland? Was the staging and style, though very different from Belvoir’s Private Lives, a kind of updating of Coward’s work?

The Kindle came to the rescue, almost instantly downloading the Bloomsbury Methuen Drama publication of Brief Encounter and, wonder of wonders, there were Coward’s original words, laid out ready for filling in all the spaces in the dialogue with so much more than the minimal directions Coward supplied for the film. The effect for me was both eminently theatrical, and effective in showing the skill, and the humanity, of Coward as a writer and a step up from where I had previously thought of him.

Not everyone agrees with me – see Murray Bramwell’s review in The Australian, September 16, 2013 at http://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/cowards-ironies-lost-in-the-action/story-e6frg8n6-1226719542652 for a different view, but perhaps more influenced by knowing the Brief Encounter history beyond Bambi and Dumbo.

© Frank McKone, Canberra

Saturday, 28 September 2013

2013: the (very) sad fish lady by Joy McDonald

the (very) sad fish lady conceived, written and directed by Joy McDonald. At The Street Theatre - Street Two, Canberra, September 28 – October 5, 2013.

Reviewed by Frank McKone

September 28

Between a rock and a hard place, there are laid out across the dividing waters stepping stones to this highly imaginative piece of folk theatre.

On the Rock lives a Greek grandmother alone with her chicken. On the Mediterranean island of a Hard Place live people who are never happy – not enough olives, not enough rain, too much rain, too windy. They tread gingerly over the stepping stones – too many of them, of course – to have coffee with the Fish Lady, so that she can read the pictures in the coffee grounds and tell them their fortunes.

But her own fortune is sad – so sad that even her chicken stops laying her daily egg – because her children live far away across the sea in Australia and she has never seen her little grandaughter.

In her imagination she becomes a fish who could swim to the other side of the world, but it is the mysterious boatman, Mister Moustache – pronounced Moustaki – who sees her sadness and magically brings her family to visit. Their coffee grounds all present the same picture. She will travel across the sea with them all the way to Australia – and so she does.

Though the chicken is so happy for her that she lays three eggs in one day, I was not sure about the chicken’s future – hopefully to cheer up the people of the Hard Place.

Over the years I have seen too much slick entertainment for young children. I have called Joy McDonald’s work folk theatre because, without pretension or the veneer of commercialism, her puppets, images and sound track tell a personal story of our times for the children of our multicultural families. Her puppeteers, Ruth Pieloor and James Scott, put on no airs while their expertise is evident not only in operating complex string puppets, hand puppets, shadow puppets and even a boat with a puppet, Mister Moustache, apparently pulling oars that really move – as well as the sad and later the smiling moon.

It is, of course, the clever design work of Imogen Keen and Hilary Talbot that makes all this possible. I guess, in the world of art criticism, the devices and imagery in the (very) sad fish lady might be called naїve art, but that’s exactly right for 3-5 year-olds. And with music by David Pereira and dramaturgical support from Richard Bradshaw, it’s obvious that this folk art theatre, as I think I should call it – like naїve art – is certainly not unsophisticated. Nor slick. Nor commercial.

the (very) sad fish lady is genuine storytelling, fascinating for the littlies and equally amusing and significant for their parents. Highly recommended.

© Frank McKone, Canberra

Reviewed by Frank McKone

September 28

Between a rock and a hard place, there are laid out across the dividing waters stepping stones to this highly imaginative piece of folk theatre.

On the Rock lives a Greek grandmother alone with her chicken. On the Mediterranean island of a Hard Place live people who are never happy – not enough olives, not enough rain, too much rain, too windy. They tread gingerly over the stepping stones – too many of them, of course – to have coffee with the Fish Lady, so that she can read the pictures in the coffee grounds and tell them their fortunes.

But her own fortune is sad – so sad that even her chicken stops laying her daily egg – because her children live far away across the sea in Australia and she has never seen her little grandaughter.

In her imagination she becomes a fish who could swim to the other side of the world, but it is the mysterious boatman, Mister Moustache – pronounced Moustaki – who sees her sadness and magically brings her family to visit. Their coffee grounds all present the same picture. She will travel across the sea with them all the way to Australia – and so she does.

Though the chicken is so happy for her that she lays three eggs in one day, I was not sure about the chicken’s future – hopefully to cheer up the people of the Hard Place.

Over the years I have seen too much slick entertainment for young children. I have called Joy McDonald’s work folk theatre because, without pretension or the veneer of commercialism, her puppets, images and sound track tell a personal story of our times for the children of our multicultural families. Her puppeteers, Ruth Pieloor and James Scott, put on no airs while their expertise is evident not only in operating complex string puppets, hand puppets, shadow puppets and even a boat with a puppet, Mister Moustache, apparently pulling oars that really move – as well as the sad and later the smiling moon.

It is, of course, the clever design work of Imogen Keen and Hilary Talbot that makes all this possible. I guess, in the world of art criticism, the devices and imagery in the (very) sad fish lady might be called naїve art, but that’s exactly right for 3-5 year-olds. And with music by David Pereira and dramaturgical support from Richard Bradshaw, it’s obvious that this folk art theatre, as I think I should call it – like naїve art – is certainly not unsophisticated. Nor slick. Nor commercial.

the (very) sad fish lady is genuine storytelling, fascinating for the littlies and equally amusing and significant for their parents. Highly recommended.

© Frank McKone, Canberra

2013: Michael Francis Willoughby in Elohgulp by Chris Thompson

Michael Francis Willoughby in Elohgulp

written and directed by Chris Thompson. Composer, John Shortis; sound

designer, Ian Blake; set designer, David Hope; lighting designer,

Alister Emerson; puppetry director, Catherine Roach. Jigsaw Theatre

Company at Courtyard Studio, Canberra Theatre Centre, September 28 –

October 12, 2013.

Reviewed by Frank McKone

September 28

Jigsaw Theatre has a long successful history (see http://www.jigsawtheatre.com.au/content/about-jigsaw-theatre-company) – but this production is not one of its best.

There are elements of the show which are very attractive – the music composition and sound design; the puppets including the rubbish-cart Drits, the suspended jelly-fish-like Assupods, and the three-headed Gludse; and the lighting hung as part of the set to complement the sound effects.

But, despite Chris Thompson’s experience, the script was rather ‘ordinary’: it seemed to be too imitative of a number of children’s stories, mostly written for younger than the middle to upper primary level which Jigsaw was aiming at, while at the same time not handling scary material which these children like, along the lines of Roald Dahl. The very realistic voice overs at the beginning of Michael’s parents arguing with each other and being angry with the boy for staying too long in the bath, with a basically empty stage, frightened me.

The pacing of the drama was too long-winded. It took ages for the Drits to establish who and where they were before Michael finally appeared down the plughole from the “bathroom up there”. Then it took more ages while he lay still on the floor before any action began. In fact, as a theatrical device, the inability of the Drits and then the Assupods to make decisions and take action was not conducive to moving the drama along. For this age group, bureaucratic committee meetings are hardly exciting.

Then there were the ducks. Though cute in themselves, their tendency to pontificate and essentially present didactic statements about what the children in the audience were supposed to learn, to my mind, is the opposite of how educational drama should work. Rather than be told “You learn a lot of things as you go along. You learn about having friends you can trust; about telling stories, and passing things on; how some things can’t last forever, and that scary things can be scariest when you are furthest away from them. And you learn that all these things are important. Even for a kid.” I would expect the drama to reveal these points through the action and the audience to discover these ideas for themselves.

Finally, I was never sure whether I was supposed to take the matter of “all the good and bad and ugly stuff that gets flushed and washed and swept away down our gutters and sinks and bathtubs” as a reality which we should all feel guilty about; or whether all this, including Michael’s being willing to take the blame, was meant to be just in his imagination while he dreams in the bath to avoid hearing his parents arguing.

Either way, it’s not clear to me what the 8-10 year-olds’ take-home message was supposed to be. Especially when the story became completely impossible as Michael leapt into what we had to suppose was a sewerage treatment pond. The relevance of his duck’s grandparent having done this in 1932 was utterly lost on me, though there was talk of a great flood in that year. Could that have meant that the flood flushed out the nasties in the pond, so the duck survived? But with no flood now, Michael would have been eaten up by bacteria in no time – though he did have some concern about drowning!

Then, in a video at the end, Michael is back in his bath – but without his ‘Dirty Duck’. So the visit to Elohgulp really happened, and his duck got left behind?

Sorry to be so nitpicking, but despite the attractive elements and the good quality performances, the production as a whole needs re-thinking in my book

© Frank McKone, Canberra

Reviewed by Frank McKone

September 28

Jigsaw Theatre has a long successful history (see http://www.jigsawtheatre.com.au/content/about-jigsaw-theatre-company) – but this production is not one of its best.

There are elements of the show which are very attractive – the music composition and sound design; the puppets including the rubbish-cart Drits, the suspended jelly-fish-like Assupods, and the three-headed Gludse; and the lighting hung as part of the set to complement the sound effects.

But, despite Chris Thompson’s experience, the script was rather ‘ordinary’: it seemed to be too imitative of a number of children’s stories, mostly written for younger than the middle to upper primary level which Jigsaw was aiming at, while at the same time not handling scary material which these children like, along the lines of Roald Dahl. The very realistic voice overs at the beginning of Michael’s parents arguing with each other and being angry with the boy for staying too long in the bath, with a basically empty stage, frightened me.

The pacing of the drama was too long-winded. It took ages for the Drits to establish who and where they were before Michael finally appeared down the plughole from the “bathroom up there”. Then it took more ages while he lay still on the floor before any action began. In fact, as a theatrical device, the inability of the Drits and then the Assupods to make decisions and take action was not conducive to moving the drama along. For this age group, bureaucratic committee meetings are hardly exciting.

Then there were the ducks. Though cute in themselves, their tendency to pontificate and essentially present didactic statements about what the children in the audience were supposed to learn, to my mind, is the opposite of how educational drama should work. Rather than be told “You learn a lot of things as you go along. You learn about having friends you can trust; about telling stories, and passing things on; how some things can’t last forever, and that scary things can be scariest when you are furthest away from them. And you learn that all these things are important. Even for a kid.” I would expect the drama to reveal these points through the action and the audience to discover these ideas for themselves.

Finally, I was never sure whether I was supposed to take the matter of “all the good and bad and ugly stuff that gets flushed and washed and swept away down our gutters and sinks and bathtubs” as a reality which we should all feel guilty about; or whether all this, including Michael’s being willing to take the blame, was meant to be just in his imagination while he dreams in the bath to avoid hearing his parents arguing.

Either way, it’s not clear to me what the 8-10 year-olds’ take-home message was supposed to be. Especially when the story became completely impossible as Michael leapt into what we had to suppose was a sewerage treatment pond. The relevance of his duck’s grandparent having done this in 1932 was utterly lost on me, though there was talk of a great flood in that year. Could that have meant that the flood flushed out the nasties in the pond, so the duck survived? But with no flood now, Michael would have been eaten up by bacteria in no time – though he did have some concern about drowning!

Then, in a video at the end, Michael is back in his bath – but without his ‘Dirty Duck’. So the visit to Elohgulp really happened, and his duck got left behind?

Sorry to be so nitpicking, but despite the attractive elements and the good quality performances, the production as a whole needs re-thinking in my book

© Frank McKone, Canberra

Thursday, 26 September 2013

2013: Shrine by Tim Winton

Shrine

by Tim Winton. Black Swan State Theatre Company, Perth, directed by

Kate Cherry, at Canberra Theatre Centre Playhouse, September 26-29,

2013.

Reviewed by Frank McKone

September 26

Tim Winton is a storyteller, and so are his characters. Alongside the road he sees a small white cross, some flowers and objects scattered around the base of a tree. This is not just a memorial, but a shrine symbolic of the person who died there. But what does it mean when among the bottles of spirits and beer there is an old thong?

He sees a middle-aged man, Adam, stop to angrily tear down the shrine and disperse all the memories. But the next time Adam drives by, he has to stop and destroy the construction again. Who keeps re-creating the shrine?

As we hear Adam Mansfield (John Howard), his wife Mary (Sarah McNeill) and the teenage girl June Fenton (Whitney Richards) tell their stories, which include the stories told by the teenagers who survived the crash, Will (Luke McMahon) and Ben (Will McNeill), and by the dead teenager Jack Mansfield (Paul Ashcroft), we discover a complexity of life of the kind that must be represented by every shrine we see along every country road.

It’s a sobering experience, yet also enlightening. And for many, as Kate Cherry said in the pre-show forum, the play provides a catharsis, a kind of cleansing of fear, especially among parents of teenage boys. Though there are humorous moments, this is a tragedy in the ancient Greek form. We know the ending before the play begins, but how did it come to this?

In Winton’s storytelling, time is a highly malleable element. All the physical items needed – the tree, the shrine, the two halves of the car, the funeral furniture, the fire on the beach, Adam’s beach house wine bar – are present on stage throughout, so scenes shift and time changes as characters move and are lit or shadowed.

The acting was excellent throughout, with to my mind special mention justified for the women, Whitney Richards and Sarah McNeill, whose roles reminded me of the Greek – of the young Antigone, who pleaded for the proper treatment of her dead brother, and an older Electra, left alone when all in the household are dead. As, in some sense, the central character, John Howard’s creation of the diversity of attitudes and feelings within Adam Mansfield was a brilliant piece of work – not so much ancient Greek, but rather very recognisable modern Australian.

For West Australians, as we might expect from Winton’s other writing, there are points of local identification – but these give the work specificity while the issues are universal. This is what makes for great storytelling, and an excellent drama on stage.

© Frank McKone, Canberra

Reviewed by Frank McKone

September 26

Tim Winton is a storyteller, and so are his characters. Alongside the road he sees a small white cross, some flowers and objects scattered around the base of a tree. This is not just a memorial, but a shrine symbolic of the person who died there. But what does it mean when among the bottles of spirits and beer there is an old thong?

He sees a middle-aged man, Adam, stop to angrily tear down the shrine and disperse all the memories. But the next time Adam drives by, he has to stop and destroy the construction again. Who keeps re-creating the shrine?

As we hear Adam Mansfield (John Howard), his wife Mary (Sarah McNeill) and the teenage girl June Fenton (Whitney Richards) tell their stories, which include the stories told by the teenagers who survived the crash, Will (Luke McMahon) and Ben (Will McNeill), and by the dead teenager Jack Mansfield (Paul Ashcroft), we discover a complexity of life of the kind that must be represented by every shrine we see along every country road.

It’s a sobering experience, yet also enlightening. And for many, as Kate Cherry said in the pre-show forum, the play provides a catharsis, a kind of cleansing of fear, especially among parents of teenage boys. Though there are humorous moments, this is a tragedy in the ancient Greek form. We know the ending before the play begins, but how did it come to this?

In Winton’s storytelling, time is a highly malleable element. All the physical items needed – the tree, the shrine, the two halves of the car, the funeral furniture, the fire on the beach, Adam’s beach house wine bar – are present on stage throughout, so scenes shift and time changes as characters move and are lit or shadowed.

The acting was excellent throughout, with to my mind special mention justified for the women, Whitney Richards and Sarah McNeill, whose roles reminded me of the Greek – of the young Antigone, who pleaded for the proper treatment of her dead brother, and an older Electra, left alone when all in the household are dead. As, in some sense, the central character, John Howard’s creation of the diversity of attitudes and feelings within Adam Mansfield was a brilliant piece of work – not so much ancient Greek, but rather very recognisable modern Australian.

For West Australians, as we might expect from Winton’s other writing, there are points of local identification – but these give the work specificity while the issues are universal. This is what makes for great storytelling, and an excellent drama on stage.

© Frank McKone, Canberra

Wednesday, 25 September 2013

2013: Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare

Romeo and Juliet

by William Shakespeare. Sydney Theatre Company directed by Kip

Williams, designer David Fleischer, lighting by Nicholas Rayment, sound

by Alan John. Sydney Opera House Drama Theatre 25 September - 2

November, 2013.

Reviewed by Frank McKone

September 25

As Tybalt, Paris and Romeo lay dead in the Capulet Tomb, and Juliet, revived from a death-imitating drug, told Friar Laurence “Go, get thee hence, for I will not away”, I found myself thinking “She’s on her own now...why can’t she go her own way now?” And indeed, in this version, she mourns her cousin Tybalt, kisses the poisoned lips of her husband Romeo, and as in Shakespeare’s script ignores the body of Paris entirely.

Paris, rather than toting a sword in this modern scenario, had brought a pistol, saying to Romeo “Obey, and go with me; for thou must die.” “I must indeed; and therefore came I hither,” responds Romeo, but Paris would not leave him alone in peace. Hiding among the graves, Romeo managed to escape the gunfire, caught Paris by surprise, disarmed him and shot him dead.