Still Life by Dimitris Papaioannou (Greece – Onassis Cultural Centre, Athens) at Carriageworks Bay 17, January 27-29, 2017.

Visual Concept, Direction, Costume and Lighting Design – Dimitris Papaioannou

Sculpture Design and Set Painting – Nectarios Dionysatos; Sound Composition – Giwrgos Poulios

Performers: Kalliopi Simou; Pavlina Andriopoulou; Prokopis Agathokleous; Drossos Skotis; Michalis Theophanous; Costas Chrysafidis; Dimitris Papaioannou.

Reviewed by Frank McKone

January 28

|

| Still Life: figure of Sisyphus |

Is this Life, still? What sort of Life is this, anyway?

So, shocked out of my almost anger at what seemed another imported pretentious European bit of ‘high art’, about which I didn't dare interview this woman, I began to think a bit more rationally about this very Still Life, with it’s long, highly-interminably long, sequences. Should I describe a bit, then analyse; or just let my feelings go?

It was like watching an early silent movie in slow motion. You remain watching as an outsider because there's little to see which engages you, especially at this speed – just an occasional visual joke for a bit of a giggle. So you keep watching, just in case. But the several scenes have no reason to be connected together, at least as far as I could work out.

Well, after the end, on the long weekend train ride from Redfern to North Ryde, I imagined some possible meanings….but here’s what happened.

We weren’t allowed in until starting time, so didn’t realise that the man seated on the stage in a low spotlight, watching us, was performing. I thought maybe he would remind us to switch off our mobiles. Then, just as we were all settled (the large Bay 17 was about two thirds full), someone marched across the stage and performed an old circus clown’s trick. He snatched the chair from under the seated man – who, of course, remained seated exactly as before, but without the chair. This event had no connection to anything else that happened for the next hour and a half.

I had read the program, which seemed to say that the work was based on the Sisyphus myth – about the man condemned to pushing shit uphill forever. So I thought I knew what the next scene was about, as a man dragged what turned out to be a wall, coated with bits of plaster which kept falling off, all the way from upstage centre to downstage centre. He rested, holding up the leaning wall against his back – until it fell onto him and he began to bodily break through, by which time we realised that there was another man (or two) behind the wall.

|

| Still Life: the women breaking through the plaster wall |

I did start to think about women breaking through the glass ceiling, even though this was a plaster wall, but in the end the last man (or it may have been a woman) standing dragged the wall away, and that was that.

|

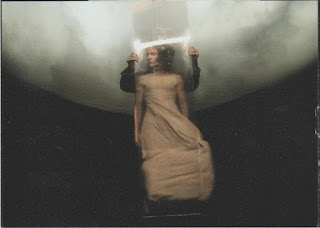

| Still Life: Woman in the Wind |

The next scene was a woman behind a transparent flexible pane, downstage centre. (Aha, I began to think – a glass wall, if not a ceiling). But no. Men came down, stood behind her and shook the flexible pane to make her long flowing dress shake about as if in a wind. Each man moved her a little way upstage, and after a very long time when she reach fully upstage, she picked up the pane as the spotlight went off, and she went off. And that was that.

After this were several more scenes: a man carrying and dropping rocks (which really did seem heavy, or was it just a sound track that made them loud when they hit the floor?). Aha, I thought, here's good old Sisyphus. But he just came and went, leaving bits of rock all over the place. And that was that.

Up to now all the men had been dressed in suits, but next was a workman with a long-handled spade – which got used in other scenes from here on. This man shovelled his own feet in a deft manoeuvre to keep walking towards downstage, and behind him was a woman carrying rocks (a bit smaller than in the previous scene), which she dropped one by one until suddenly dropping them all at once, so he had to shovel them aside. Apparently he was very sexy, so she dropped his daks and underpants so we saw his bare backside. He leaned forward (facing upstage) while she climbed up (in bare feet) and balanced (she actually fell off first time – in the act, or not?) and so he carried her on his bare bum, oh so slowly, back upstage until they disappeared. And that was that.

That looked like the end of anything obviously to do with Sisyphus. For the next very long time people (back in suits, I think) found the ends of very long strips of gaff tape stuck to the wooden stage floor, which made fingers-down-the-blackboard type noises with deeper echoes because the floor was made of hollow rostra boxes, as they spent a very long time ripping all these strips from straight and circular lines, knocking away bits of plaster and rocks as they went. When that was finished, then that was that.

Then a man in a suit, with some help from another one, managed to balance on things like rather large bricks. He was good, but when that was done, that was that.

|

| Still Life: Sunrise with Shovel |

But then the shovel got used to push up as far as it could reach into the lower surface of the translucent huge balloon-like structure which had been hanging all the time from the stage roof, with dry ice mist making it look like a cloud. When the bottom was pushed up, and a large circular Fresnel lamp lit up from upstage pointing just about horizontally at me in Row N, the whole filmy material floated, giving an impression very much like a sunset over water with a more orange light, and while the shovel man (in a suit, not a workman) and another sat down to watch on the stage (with their backs to us), the light changed and became a sunrise.

Visually, the effect was wonderful, but when it finished, that was that. Until out of upstage gloom came a fully set-for-a-sumptuous-lunch table, moving very slowly downstage especially because the bottom of each leg was placed on the top of a man’s head – no hands (except that some changed, like soccer players coming on from the bench, and hands were used to make the transition).

This table was carried off the stage onto the auditorium floor, at which point chairs appeared and all the cast sat down to eat. The audience was not invited – in fact we were completely ignored. So a number of people decided this was the end and started leaving the theatre. There was a little more action, but nothing significant, and so the audience decided it was time to clap. So the performers got up and left via the stage wings, lights went down, we clapped more and the cast came out for a conventional ‘curtain’.

And that was that.

In my later wondering, I went back to the program. It quotes Albert Camus referring to the Sisyphus myth, saying “The struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Then I thought, remembering the broken paving in the streets of a very poor-looking Athens when I was last there, perhaps all those broken rocks and plaster walls are meant to represent the Greek economy. But then is the sumptuous lunch supposed to mean, like Camus’ Sisyphus, just be happy. Or was the lunch entirely cynical, saying it’s OK for those who can afford lunch, and don’t pay their income tax, but be damned to the rest of the Sysiphuses, men and women, struggling forever with their rocks, walls and gaff tape.

The program also refers to Dimitris Papaioannou as “Rooted firmly in the fine arts” and becoming “more widely known as the creator of the Athens 2004 Olympic Ceremonies”. So that’s that, then. I wonder.

© Frank McKone, Canberra