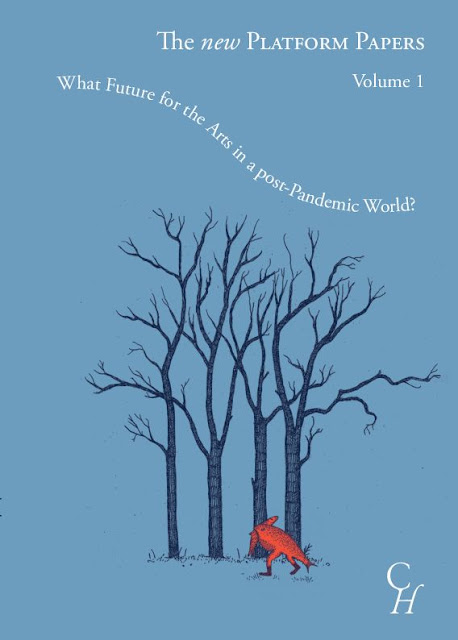

New Platform Papers No 1, Currency House, November 2021.

Contact:

Martin Portus Phone 0401 360 806

mportus2@tpg.com.au

Preview by

Frank McKoneThe Platform Papers series published by Currency House, previously directed by

Katharine Brisbane, is taking a new approach, under the new General Editor, theatre director and academic

Julian MeyrickKatharine

provides in her Christmas Greetings an outline of changes, especially

in the status of women, that have taken place over the two decades of

her leadership in setting up Currency House, following her stepping down

as publisher of Currency Press.

Rather than each Platform Paper

being an essay by a single expert contributor, this New Platform Paper

contains five papers, with additional material:

No 1. Imagination, the Arts and Economics Introduction: A Snail May Put His Horns Out,

Harriet Parsons Models, Uncertainty and Imagination in Economics,

Richard Bronk What’s Wrong with Cannibalism?

Jonathan Biggins and

John Quiggin

You Can Sing (Averagely)!

Astrid Jorgensen Afterword: Looking Back and Looking Forwards,

Ian MaxwellRather

than offer a summary of the complex arguments and practical experiences

presented by such a variety show of commentators, here is a selection

of quotes which hopefully will stir your social, political and artistic

interests and knowledge.

Julian Meyrick explains:

The

first issue of the New Platform Papers published in this volume arose

out of an event which will be central to the series from now on, an

annual Authors’ Convention. The Convention itself was the initiative of

my colleague, the new Director of Currency House and Katharine’s

daughter, Harriet Parsons. A brilliant addition to our activities, the

Convention is a two-day public gathering where we invite the authors of

Platform Papers to come together to reflect on a given theme.

Harriet Parsons (Wurundjeri country)

Introduction: A Snail May Put His Horns Out

We

have to decide what changes we are willing to make if we are to plan a

route, not just out of the pandemic, but off the dangerous course we

have been following for the past forty years. The arts may seem an

unlikely point man for this operation. We have become more like a snail

than a butterfly, withdrawn inside the protection of its shell, but as

the eighteenth-century radical Thomas Spence once wrote, ‘a snail may

put his horns out’.

This first volume of the New Platform

Papers is devoted to exploring how our imaginations became captives of

the ‘dismal science’, and the role the arts can play in leading the way

out.

Richard Bronk (United Kingdom)

Models, Uncertainty and Imagination in Economics

The

coordination properties of models and their associated narratives—their

tendency when internalised to frame expectations and influence

behaviour and outcomes—makes them an instrument of corporate or

government power. And this power may—initially at least—be in inverse

proportion to the degree of humility with which the narrative or model

is promulgated.

The poet, Percy Bysshe Shelley, underlined the role of imagination in sympathy and therefore morality in his Defence of Poetry:

A

man, to be greatly good, must imagine intensely and comprehensively; he

must put himself in the place of another and of many others; the pains

and pleasures of his species must become his own. The great instrument

of the moral good is the imagination—and poetry administers to the

effect by acting upon the cause.

Such sympathetic

identification with the plight of others is often seen as the

quintessential opposite of the narrow self-interest of homo economicus.

…we

all have no choice but to imagine the future, interpret the creative

interpretations that others place on their predicaments, and invent new

ways of making sense of our own.

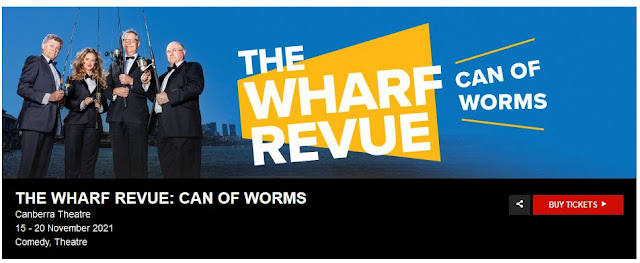

Jonathan Biggins and John Quiggin (Awabakal and Worimi country / Turrbal and Jagera country)

What’s Wrong with Cannibalism?

Jonathan Swift’s essay A Modest Proposal

was prompted by the British national debt crisis of 1729. Having

offered conventional solutions in a number of essays, he turned to

satire in frustration, proposing that landlords eat the children of

their poor tenants:

I grant this food will be somewhat dear, and

therefore very proper for landlords, who, as they have already devoured

most of the parents, seem to have the best title to the children …

Swift’s

A Modest Proposal seems, yes, a ludicrous idea, but then look at

Airbnb, where you monetise your family home. The home was the sacred

hearth of the family. But then someone came up with the idea of selling

part of it to strangers on a nightly basis. We recently toured to Orange

in regional New South Wales. It has 364 Airbnbs, but no-one can rent a

house there.

At an artistic level, much of our cultural policy

is now being dictated by social media platforms, and artists are

increasingly self-censoring. We were recently told not to portray

non-Caucasian characters in the Wharf Revue. We were portraying Xi

Jinping and Kim Jong-un, two of the most powerful people in the world. I

find it extraordinary that satirists are now being told who they can

and can’t offend. I would have thought the point was to offend

everybody.

Harriet Parsons asks: So is the universal basic income the answer for the arts?

JQ:

I’m certainly a proponent of a version of the universal basic income,

which is the level of income guarantee, which would include a basic

living standard for artists engaged in creative work. It differs in the

sense that you don’t give it to Gina Rinehart and try to extract it back

through taxes, you only expand the provision of basic incomes. But that

would provide a basic income to anybody who wanted to apply themselves

to creative work. That is something we could and should do.

Astrid Jorgensen (Turrbal and Jagera country)

You Can Sing (Averagely)!

I

could not wrap my head around the fact that teenagers were spending

every second of their lives consumed by music while simultaneously

proclaiming to hate Music, the subject. They would walk into the

classroom with their favourite singer blasting in their headphones, then

take the headphones out, slump in their chair and despise singing with

me for 50 minutes. I started to worry that I was ruining music-making

for children, which was a heavy burden to bear.

[Astrid left

school teaching to set up the well-known Pub Choir, which in the

pandemic lockdowns became Couch Choir online, attracting participants

from all over the world.]

But there was one thing still

bothering me. None of these choirs reflected me in any way. Each of my

seven choirs were either made up of kids forced to sing by their

parents, or were mostly white, semi-retirees. There is nothing

unpleasant about working with either group. But as a 20-something Asian

woman myself, it was confusing to me that none of my peers wanted to

sing.

So in 2017, after years of friends declining to sing with

me, I wrote a list. On it, I put every excuse I’d ever heard about what

stopped somebody from joining a choir:

Auditions

Time commitment

Having to compete/perform

Reading sheet music

Unfamiliar repertoire

General choir lameness

Having a bad singing voice.

I determined to solve all of these roadblocks. Thus, Pub Choir was born.

Not

always in a pub, the trademarked name, Pub Choir, describes my musical

act. It’s a ticketed show during which I transform an audience—any

audience—into a functional choir.

I believe that Pub Choir

gives people the opportunity to embrace and value mediocrity and truly,

madly, deeply embrace their averageness. There is a freedom in a crowd

where you are genuinely unimportant. Nobody believes that they have

become a better singer at Pub Choir. They just feel less afraid to share

whatever horrible voice they have. If one person forgets what to sing,

someone nearby will remember. Some people sing flat, some sing sharp,

some sing too early, some too late and the overall effect is a rich,

full, electrifying average. Our audiences reclaim music-making back into

their lives, realising that singing belonged to them all along.

The diversity within Couch Choir

participants was remarkable. In one song we had 5,000 participants from

45 countries. We received submissions from places we had never

considered visiting, like Kazakhstan and Norway. People sent videos from

their farms, their wheelchairs, from houseboats, using sign language.

They were younger, older, more colourful. Couch Choir was the

distillation of what I had always hoped Pub Choir would be: regular,

diverse people feeling personally empowered to contribute to the whole.

Sure,

it’s not peer-reviewed research, it’s just 613 people who chose to

participate. But when 100 per cent of them self-report that their mental

health is improved by joining in, it’s worth taking note. Singing—even

online—made them feel happier, more connected and more hopeful. And they

thought it was an experience worth fighting for. Art has always been

more than just entertainment or a distraction. Art can heal us.

Ian Maxwell (Cadigal and Darramuragal country)

Afterword: Looking Back and Looking Forwards

Exhaustion,

then, is integral to the [arts] field at the best of times. In the

context of the acute crisis of the current Covid-19 epidemic, the arts

eat their young…. [leading to] three questions, which were put to the

Convention for further discussion. Four key themes emerged. First, the

proposition that art and culture are fundamental to the sustainability

of society; second, that those engaged in the fields of art and culture

do not have the capital to support them; third, that the arts are

exhausted; and fourth, that its professionals have been pitted against

each other in the competition for resources, with the result that the

sector has become fragmented and unable to advocate for its interests as

a whole.

Ambiguity is the strength of art, as well as its

weakness. Historically—indeed from Plato onwards—the protean,

make-believe, liminal nature of theatre—and the recent genres that take

up the even more equivocal trope of ‘performance’—has generated profound

anxiety and moral panics.

Our challenge is to resist

reprising old arguments that belong to the past, and instead peer

through the lens of new experiences with the eye of imagination. That, I

hope, is the project Currency House has set before us, and towards

which the inaugural Convention of 2021 has made the critical first step.

For interviews, review or purchase, please contact Martin Portus.

© Frank McKone, Canberra