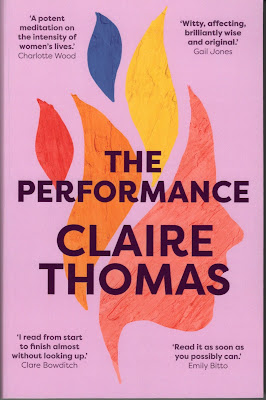

The Performance

|

| Published by Hachette Australia |

The Performance. A novel by Claire Thomas. Hachette Australia, 2021.

Reviewed by Frank McKone

When

watching a performance in a theatre, I often wonder what is going on in

the heads of others in the audience. You hear the occasional cough,

and sense if the cougher seems embarrassed or seems to have no concern

for the feelings of others. I laugh, and shrink in a little as I

realise I’ve laughed too loud.

As a critic, my feelings in

response to what’s happening on stage are mixed with thoughts of many

kinds about the technical elements like casting, costume and

hairdressing, lighting, sound, use of voices, choreography of movement,

and even placing of this play and this production in the history of

theatre. If thoughts about private matters arise, as they can, of

course, I will try to set them aside and re-focus my attention on the

performance.

As I write this, I seem to have become a character, not mentioned by Claire Thomas, in her audience watching Happy Days

by Samuel Beckett. Except that I am remembering the production

directed by the one-time Canberra High School highly respected principal

and noted theatre identity, Ralph Wilson, in 1991 – in what is now

affectionately known as the Ralph Wilson Theatre.

In The Performance,

the performance is clearly in a professional theatre. Margot is an

established academic and subscriber, Summer is an usher and budding

actor, while Ivy is a middle-aged arts enthusiast who has brought her

friend Hilary. She thinks “Hilary was the obvious person to bring

along. They studied Waiting for Godot together in high school,

an experience that marked the beginning of Ivy’s passion for Beckett, or

SB as she came to refer to him.”

“Summer has once again missed

the beginning of the play” because she’s not “on Stairs” this night,

but “on Door” where “her main task is handling the latecomers in the

foyer". Margot is “almost late”, “shuffling in a balletic first

position along the strip of carpet between the legs of the

already-seated people…and the chair backs of the row in front”.

And

I immediately thought of the occasion in the Canberra Theatre, when my

wife and I were amused, fortunately not in the same row as their one

nearer the stage, watching the tremendously tall Margaret and Gough

Whitlam, one-time Prime Minister of Australia, doing a more commanding

kind of shuffle. Then I thought, there’s another book everyone should

read: Margaret Whitlam – A Biography by Susan Mitchell (Random House, 2006).

That’s what I love about The Performance.

It just naturally takes you into thinking about things, just like the

characters in the story. They are making connections, thinking and

re-thinking about what’s happening on stage and what’s been triggered in

their memories and about what’s happening around them at the moment.

It’s an absorbing book to read. Though I had to take a break of a few

days at interval, I understand entirely why musician and writer Clare

Bowditch commented “I read from start to finish almost without looking

up”.

I meant “at interval” literally. The novel has a theatrical structure. Before interval there are six parts, simply numbered ONE to THREE, focussed in turn on Margot, Summer and Ivy; then FOUR to SIX following each of them up later in Act One.

Then comes THE INTERVAL – a short play, in four scenes, by Claire Thomas. The characters listed are

SUMMER, female, early 20s, theatre usher

PROFESSOR MARGOT PIERCE, female, early 70s, audience member

IVY PARKER, female, early 40s, audience member

HILARY FULLER, female, early 40s, audience member

JOEL, male, mid-20s, audience member

APRIL, female, mid-20s (screen and voice only)

After The Interval, there are parts SEVEN to NINE, again following up Margot, Summer and Ivy in order through Act Two of Happy Days. You don’t need to have seen or read Happy Days,

but you certainly get to feel you appreciate Beckett’s work as each of

the three respond to particular images, sounds, words and quality of

light which spark their thoughts and feelings.

It is Ivy, then,

through whose eyes we see the end of the play, in which Winnie is buried

up to her waist in Act One and up to her neck in Act Two. Ivy notes

“When the lights darken to allow a surge in applause, Winnie will not

climb out of her trap to appear whole again like a magician’s assistant

whose destruction was an illusion. Winnie will stay inside the mound.

She will not appease the audience.”

This is where the novel comes

to its fruition, matching the insights of Samuel Beckett and the

director and designer of his play (whom I take to be Claire Thomas,

since there is no reference to any actual performance) with the

inter-related experiences of the three women, and the traps they may or

may not climb out of.

I can only agree with the other readers

quoted on the cover of this novel: “Witty, affecting, brilliantly wise

and original” (Gail Jones); “A potent meditation on the intensity of

women’s lives” (Charlotte Wood); and “Read it as soon as you possibly

can” (Emily Bitto).

|

| First published by Grove Press NY 1961 First production at Cherry Lane Theatre, New York City on 17 September 1961 |