‘So That You Might Know Each Other’ – Faith and Culture in Islam. Exhibition at the National Museum of Australia, April 20 – July 22, 2018. Free Entry.

Reviewed by Frank McKone

May 6

Museum

people love to tell you how many ‘objects’ they have in a collection.

For this exhibition, I prefer the French word ‘objets’, as in objets d’art. ‘So That You Might Know Each Other’

is certainly not about exhibitionism. The items on display are from

the daily lives of people, from the many ordinary to the occasional

wealthy, shaped and decorated in beautiful ways.

Is

that what you expected from the rest of the title, ‘Faith and Culture

in Islam’? Perhaps not. There is as much to learn from the story of this exhibition as there is to see in

the exhibition. Senior curator Carol Cooper’s quietly effervescent

enthusiasm shines through. An overhead spotlight projects an outline of

the map of the world from Italy in Europe to China in the Far East, and

round the corner to Australia in the South.

It all began with the Roman Catholic Pope Pius XI in 1925 and Fr Nicola Mapelli nearly a century later. Let me explain.

I

think of the NMA as a dynamic museum, not stuffed with objects from the

past for people to stare at, but always mounting changing exhibits

which illuminate not only the past, but the present too, with

implications for the future. Songlines – Tracking the Seven Sisters is a terrific example (reviewed here 17 November, 2017).

The story of ‘So That You Might Know Each Other’ begins

in a museum set up in the Vatican by an Italian pope, Ambrogio Damiano

Achille Ratti, perhaps looking forward to the present Pope (who hails

from South America). Pius XI took the meaning of ‘catholic’ to suggest

the church should collect in a museum – now known as the Anima Mundi –

items which would show the philosophy of being ‘universal in extent –

involving all’ (Macquarie Dictionary).

As I see it, there could

be two motivations for this decision. Translated as ‘the soul of the

world’ it might be seen as Roman religious colonialism. But I suspect

that Pius XI also thought of bringing to the Vatican, which in those

days was an insular organisation, the ‘life’ of the world to make his

administrators and Italian Catholics aware of the variety of other

peoples’ beliefs and practices. It is this interpretation which I’m

sure Fr Mapelli, and the Director of Vatican Museums, Barbara Jatta, are

working from. It makes the translation something more like ‘Welcome to

the World’.

Though I, personally, don’t subscribe to any

religious belief, I see in their work the human rights and understanding

value in a cooperative venture with the Sharja Museums Authority of the

essentially Muslim society in the United Arab Emirates. I don’t doubt

that Jorge Mario Bergoglio, who was elected the 266th pope of the Roman

Catholic Church in March 2013, becoming Pope Francis, and the first pope

from the Americas, fully supports cross-cultural cooperation. His

choice of the saint’s name ‘Francis’ is obviously significant, and bodes

well for human rights.

On the other side of the hand-shaking is a

human rights interpretation of the essential Islamic text, the Q’ran.

Though I, again personally, have concerns about the parts of text that

seem to be divisive, encouraging fighting in defence against believers’

enemies, there are two quotes which underpin this exhibition.

In Chapter 57, Iron,

after the early prophets Noah and Abraham, “We sent other apostles, and

after these Jesus son of Mary. We gave him the Gospel and put

compassion and mercy in the hearts of his followers.” (trans. N J

Dawood, Penguin 1956)

The other includes the title of the

exhibition: "O Mankind, We created you from a single pair of a male and a

female and made you into nations and tribes, so that you may know one

another. Verily the most honored of you in the sight of God is he who is

the most righteous of you" (Chapter 49, The Chambers). This

translation is from an excellent paper by Abdul Malik Mujahid, delivered

at the International Council of Christians and Jews (ICCJ) Conference,

Istanbul June 23, 2010.

http://www.iccj.org/redaktion/upload_pdf/201011262022430.Mujahid_keynote.PDF

In this paper, Abdul Malik Mujahid explains:

In

this brief verse, Islamic scholars have been able to draw several

fundamental Islamic principles which are reaffirmed elsewhere in the

Quran and the Prophet’s teachings:

God addresses all of humanity, not only the Muslims.

God says that He created us from one man and one woman, thus making us all

brothers and sisters.

The verse invalidates the claims of superiority due to one’s birth by stating that all

are born through a similar process, i.e. from a male and female.

God is the One who made human beings as part of tribes and nations as a means

of identifying and differentiating. This is not meant to be a source of superiority

or inferiority, nor as a contributing component of tribalism, caste systems,

nationalisms, colonialism or racism.

The only measure of greatness among human beings is at the individual level, not

on a national or group level, based on the characteristic called “Taqwa” in Arabic.

This word means God-consciousness.

This singular criterion of preference, Taqwa, however, is not quite measurable by

other human beings since it deals with the inner self. Therefore, human beings

must leave even this criterion to God to decide rather than using it to judge each

other. At the same time though, this principle does not mean that we are unable to

differentiate between right and wrong behavior, nor does it prevent us from acting

against wrong actions. Rather, it discourages the human tendency to ‘sit in

judgment’ of others.

And

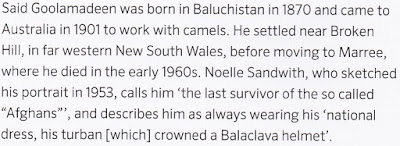

so, as you explore the extensive exhibition at the National Museum of

Australia, you will see objects from a camel’s saddle, a desk calendar,

a lectern, an embroidered wedding shawl, among “over 100 precious 18th

to 20th Century objects from over twenty countries” illustrating “the

evolution of Islam across the globe and celebrates diverse Muslim

societies from the Middle East, through to Africa and India, China and

South East Asia” – and including objects and photos of Muslims in

Australia, from early contacts with Indonesia several hundred years ago

to those who came in substantial numbers from 1860.

Though the

catalogue might seem expensive at $30, it is a wonderful record of the

exhibition to keep, not only for the excellent quality of the photos of

the objects, but especially for the detailed historical and cultural

information in the text.

We can be justifiably proud of the

humanity expressed in the meeting of the minds of Fr Nicola Mapelli,

Ulrike Al-Khamis and Carol Cooper in bringing together the best of the

collections in the Vatican Anima Mundi Museum, the Sharjah Museum of

Islamic Civilization and our own National Museum of Australia. As Dr

Barbara Jatta writes: “As I followed the preparation of this exhibition,

I was sincerely struck by the beauty and sophistication of the Islamic

world – I saw firsthand the refined productions of people living across a

vast area stretching from Africa to Australia.”

For Australians

now as much as for Pope Pius XI in 1925, such appreciation of others’

beliefs and cultures is essential for a better future around the world.

This exhibition is not to be missed.

© Frank McKone, Canberra

No comments:

Post a Comment