One Man In His Time by John Bell and Shakespeare. Bell Shakespeare at Canberra Theatre Centre Playhouse, Wednesday and Thursday, April 14-15, 2021.

Reviewed by Frank McKone

April 14

Conceived and performed by John Bell

Lighting Designer: Ben Cisterne

Stage Manager: Eva Tandy

__________________________________________________________________________________

Actors

are the only people who can be trusted, because we all know they are

pretending. But, said the actor John Bell, I wouldn’t trust an actor.

I’m

not quoting his words exactly – my 80-year-old memory, two months

younger than Bell’s, is a disgrace in comparison. Not only can he give

us many of Shakespeare’s most significant speeches, he makes One Man In His Time a masterclass study of that other actor/writer’s universal truths.

His

audience ‘got it’ when it came to issues like political leadership in

modern times, well before the ‘T’ word was spoken. Manipulative

advertising men as Prime Ministers didn’t even need to be mentioned by

name.

Trust in Shakespeare is the message, as Bell

has done throughout his life in acting roles, as a director and founder

of the Bell Shakespeare theatre company, “Thanks to an innate love of

theatre and the inspiration provided by two wonderful high school

teachers.” His show was devised to celebrate Bell Shakespeare’s first

30 years as arguably the longest-lasting and only truly national

Australian theatre company.

I found myself feeling inspired by

John’s elucidation of that other writer/ performer/ director man in his

own time (probably b. April 23rd 1564 – definitely d. April 23rd, 1616);

but I also felt that I would love to understand more about our own

famous theatre man in his time (November 1940 – 2021 ongoing…, or at

least since about 1955 when those teachers grabbed his attention).

His

illustrations from the History plays, the Roman plays and especially

Hamlet, King Lear and The Tempest – and his demonstrations of how to

play the enormous variety of Shakespeare’s characters – revealed, with

the immediacy of an actor we undoubtedly could trust, exactly the

attributes Bell has described in his note “From John Bell”:

“In

putting together this meditative piece about Shakespeare I avoided

structuring it around any one theme in case it got too academic.

Instead I have chosen to focus on just a few of his attributes: his

compassion, empathy, shrewd understanding of politics and power

structures, his earthy humour and, of course, his peerless poetic

language which,” he says, “will go on living only if we go on speaking

it and listening to it.”

My interest in knowing more about

the real John Bell has been stirred in recent times by reviewing what I

have seen as a new genre which I have named Personal Theatre.

The most recent is Stop Girl, a 90 minute piece at Belvoir, Sydney, written by foreign correspondent journalist Sally Sara.

Her central character, “Suzie”, is a true representation of Sally’s

personal reaction, post traumatic stress disorder, following years of

war-zone reporting. Her play is double-edged, showing the horror of war

for others as well as for herself, even as a professional objective

reporter.

Another extraordinary piece, by Canberra dance artist Liz Lea reveals her lifetime experience, through a solo dance with spoken word, Red, of suffering from endometriosis.

An experience of a quite different kind, but again effecting a change of life, is shown in My Urrwai, in which Ghenoa Gela,

again in dance and voice, tells her story of re-engaging with her

original culture in the Torres Strait after a childhood in Brisbane.

This is a story of gaining new appreciation and personal strength, in

life and as a performer.

I would look forward to, perhaps, something called When the Bell Rings.

I

first saw John Bell when “In 1964 he was a sensational Henry V, with

Anna Volska as Katherine, in an innovative Adelaide Festival tent

presentation. The Sydney Morning Herald called him ‘a possible Olivier

of the future’”. Since then I have maintained an interest in his career

before and after establishing Bell Shakespeare, and since my retirement

from drama teaching in 1996 I have reviewed his work as performer

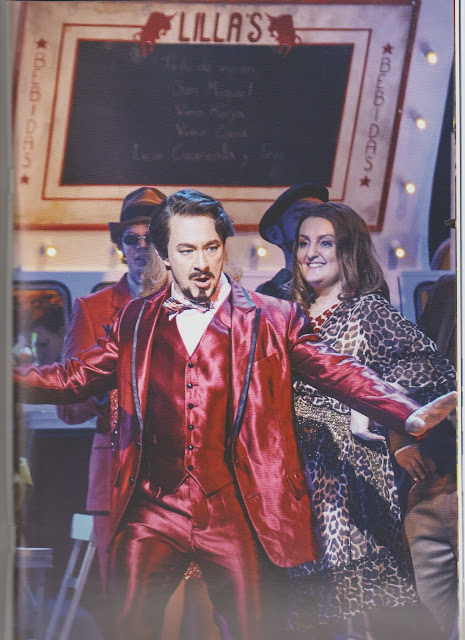

and/or director of 9 shows, from King Lear to Carmen; from the Bell Shakespeare art exhibition The Art of Shakespeare to Christopher Hampton’s translation of The Father by Florian Zeller.

[https://liveperformance.com.au/hof-profile/john-bell-ao-am-obe/ ]

[https://frankmckone2.blogspot.com/search?q=John+Bell ]

Of The Father,

I recorded “Of course, especially for John Bell playing Anne’s father

André, the short scenes are not so simple. As he has said ‘I find

this text particularly tricky to learn – and I think I speak for the

other actors as well – because it’s very fractured and you need to make

your own links between phrases. It’s just short grabs of text, which

are hard to learn. It’s easy to learn a slab of Shakespeare, for

instance, or Chekhov. They write these long passages that have an

internal logic, that might even rhyme’.”

Watching The Father,

I also found myself, already in 2017, beginning to worry about how I

might cope with the onset of dementia “when you, if you are unlucky,

reach a late stage of dementia where memory becomes completely

unreliable but your feelings in reaction to others – who are by now

caring for you full-time – are just as strong as ever, even though you

are misinterpreting reality. It’s even worse when you realise that you

don’t actually understand things at all.” I was amazed at Bell’s

performance, considering questions like what will John Bell do when his

memory gets as bad as mine, and how does an actor know when s/he is

acting or not; or knows, as my mentor Ton Witsel put it, when you are

only ‘acting acting’?

(Ton worked at the Old Tote as Mime and

Movement Director in the 1970s with John, who had been the original

Director, and was then Associate Director for the later tour to the

South Pacific Festival of Arts in Suva, Fiji, of the iconic new wave

Australian play, The Legend of King O’Malley by Michael Boddy and Bob Ellis). [https://evols.library.manoa.hawaii.edu ]

So, maybe I was hoping for Two Men In Their Times – William Shakespeare and John Bell, but perhaps that’s an unfair expectation. One Man In His Time at a time is surely enough.

© Frank McKone, Canberra